100 years of ski fashions: looking sensible rather than smart

The first 100 years – 1861 to 1961

Contributed by Wendy Cross

When the first skiers of Kiandra schussed Township Hill, none would have dreamed that in less than a century, a multi-million dollar international industry would have grown up in response to a demand for not only ski equipment but also special clothing to wear while using it.

The well dressed skier in the second half of the 19th Century wore whatever clothing he or she would have donned for almost any outdoor activity of the times. The well-to-do graced the slopes in neatly pressed natty apparel – suits for the men and wasp-waisted, full-skirted dresses for the ladies – and those who earned their living as miners, stockmen or labourers wore whatever they felt was necessary to ward off the cold. Carnival days were an exception. Then, banker and rouseabout alike turned up in their Sunday best.

The famous Charles Kerry photographs of the 1896 and 1898 Kiandra Carnivals show a wide sartorial range. Most of the men wore sober business suits complete with waistcoats and watch-chains, stiff white collars and dark ties. A few were more casually attired, minus tie but with white shirt buttoned at the throat, and some opted for moleskins instead of suit trousers. Surprisingly, few wore sweaters but to a man, they all wore hats and gumboots. The womenfolk, whose bustles and tightly corseted waists thrust their bosoms forward pouter-pigeon-style, were clad for the most part in dark clothing, often including heavy woollen outer cloaks. Most topped their upswept hair with straw boaters, although a few of the older ladies opted for huge frilly bonnets similar to those worn by children. Their skirts trailed on the snow, but younger women daringly wore theirs a few centimetres above the ground. Most women wore galoshes over tightly-buttoned ankle boots but a few followed the lead of the men by sloshing about in unglamorous gumboots. Except for the footwear, the entire community could just as easily have been at a church picnic.

It was to be many decades before Australian skiers realised that although local temperatures were rarely as low as those of Europe in winter, the dangers of exposure were just as real. They continued to ski in ordinary winter clothing, with oilskins and woollen scarves the only concession to blizzard conditions. Fortunately, thick woolly underwear was the norm for everyday winter activities and this usually provided adequate insulation on the slopes, so it was 1928 before any Australian skier perished from hypothermia.

When the Hotel Kosciusko opened in 1909, there was much twittering in Sydney’s fashionable drawing rooms about the right apparel for making an impression at the new society watering hole. Percy Hunter, ever ready to give his opinion on anything whatsoever relating to skiing, gave advice on clothing in an article in the June issue of the monthly magazine The Lone Hand:

The most comfortable and convenient ski or tobogganing dress consists of a good sweater, bloomers, and a short skirt of smooth-faced tweed or serge. It is important to select a smooth material, as a rough or hairy surface holds the snow crystals and quickly becomes wet. Rubber boots, colloquially known as gum, will keep the feet absolutely dry, and they may be worn over two pairs of stockings. An experienced lady ski-runner recommends the wearing of a thin pair of, say, cashmere hose, and over these a thick knitted pair, the tops of which are folded over the boots. This fold keeps the snow from dropping down the boot when the wearer falls or plunges into deep snow. To prevent sunburn on the snow it is wise to wear a close cap with a good motor veil. Men need no special wear with the exception of gum boots. These are essential. Men should have plenty of woollen underclothes and, for preference, smooth-faced tweed clothes. Everyone would be well advised also to include in their kit a stout waterproof ulster in case of snowstorms.

Hunter’s advice, though sound, was not always heeded and many of those who skied at Diggers Creek wore extremely hairy outer clothing. As a result, they accumulated more and more snow as the day wore on, until some were quite literally bowed down by the extra weight they carried around.

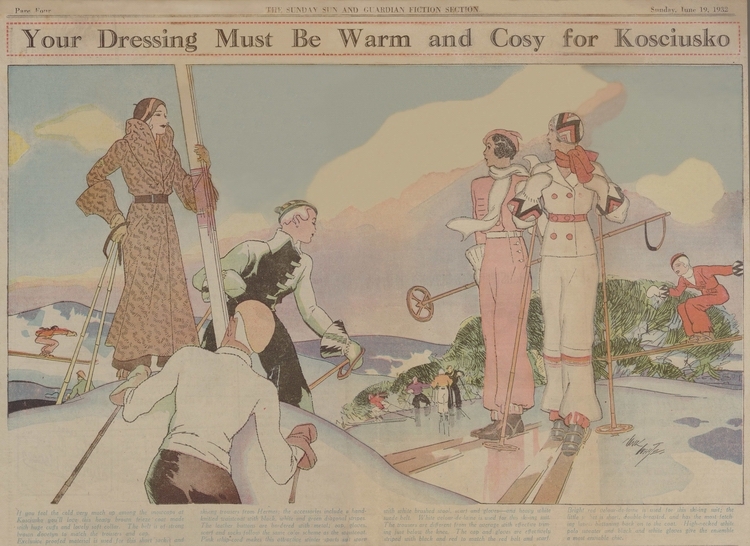

Gradually, women skiers began wearing their skirts a little shorter and the more daring discarded them altogether, in favour of extremely baggy ‘ski pants’ of gabardine. During World War 1, most skiers, both male and female, took to the baggy pants but a few men preferred plus-fours or riding breeches combined with golf socks or puttees. The really fashion-conscious completed their outfits with a matching gabardine jacket but the majority wore whichever garment seemed most appropriate for the weather at the time. Hats ran the full style gamut, though most favoured close-fitting visored caps. Venn Wesche, who made his mark during the Twenties and Thirties as an accomplished racer, also achieved fame of a quite different kind for wearing what his best friend Stewart Jamieson, editor of the Australian Ski Year Book, described in 1930 as ‘…the worst hat ever seen on the Australian snowfields’. The hat was later reported by Jamieson to have been eaten by one of the Chalet dogs, causing the unfortunate canine’s early demise.

In 1920, when the Kosciusko Alpine Club published some advice for its female members in its Year Book, styles had changed little. The KAC’s expert advised serious lady skiers that the proper costume comprised coat, skirt and knickerbockers, although the skirt could be left off if desired. Knock-kneed ladies were advised to make their knickers hang over at the knees. ‘This can be done without giving them any semblance to bloomers,’ the writer assured them.

As the Twenties progressed, riding breeches and puttees gained favour with women as well as men and flappers favoured long knitted scarves which hung to their knees. However, towards the end of the decade, the first ‘tailored’ ski pants appeared. These were actually baggy at the ankles and allowed for several layers of flannel underwear if the weather happened to be inclement.

Ski boots were very lightweight and often ill-fitting, so most skiers wore spats over the top, to keep out the snow. In some circles it was also de rigueur to wear baggy navy gabardine ‘apple-catchers’ offset by natty white or yellow cable knit socks. The first question asked by a new skiing girlfriend would be foot size. Brandishing her knitting needles, she would then demonstrate her devotion to her beloved by producing a pair of such socks.

In July, 1933, The Melbourne Herald’s fashion writer made it clear that she disapproved of women wearing riding breeches.

Special clothes are very nice but they are not really essential for men, though they are for women. Women look best skiing in long trousers that tuck into the boots, and are worn with a shirt or belted coat doing up to the neck. They look very ugly skiing in riding trousers and leggings or gaiters.

A year later, that unrivalled arbiter of good taste for middle-class suburbanites, The Australian Women’s Weekly, issued a pronouncement on the increasingly intricate ins and outs of ski fashion:

The most dangerous pitfall in buying skiing clothes is colour. One sees many bright and colourful ski-costumes in magazines and shops, but, according to those who ski in Switzerland, and other winter resorts, too much colour is the sure sign of the amateur.

A touch of brilliance against the snow is effective, and this is achieved in sweaters, scarves and caps. A plain dark gabardine suit, single or double-breasted, is the classical style. Let it be navy, black, dark green, dark brown or grey.

Quite obviously, Australia’s women skiers did not want to be taken for amateurs. Almost without exception, they stuck rigidly to sombre colours relieved only by an occasional ‘touch of brilliance’ as suggested by the Weekly. Sydney fashion writers covering the Ski Club of Australia Championships at Charlotte Pass in 1936 reported that socialite Mary Hordern wore ‘a navy blue suit and new hat of blue gabardine in peaked shape, with open crown, and fitted at the back to enclose her long hair. Patsy Finlayson borrowed a design from the Tyrol for her ski hat. Its vivid green with a scarlet feather worn straight up the back was much admired. Ann Bevan was the only skier not in navy blue or black gabardine. She daringly wore a chocolate brown plus-fours suit, worn with a brown snowcap and a brown scarf with white polka dots.’

The formality of social convention in the years before World War 11 had a direct influence on ski fashions. Many men wore white business shirts and ties with their apple-catchers and for a time, women too wore ties as on-slope fashion accessories. Public appearances apres ski demanded even greater formality. For example, when the Australian team sailed from Sydney in August, 1936, to contest the Interdominion Championships in New Zealand, its female members were photographed for the newspapers, smartly clad in suits, hats, gloves, fur tippets and even corsages.

‘Vorlage’ ski pants, with tapered legs and elastic under the foot, were invented in Europe just before the War, and caused the prompt demise of apple-catchers and the like. Nevertheless, since elasticised materials were not developed until the late 1950s, vorlage pants were cut extremely wide for about two-thirds of their length, to compensate for the reduced ‘give’ caused by the foot-strap. Most were made of ever-reliable gabardine, whipcord or loden cloth, the heavy, napped fabric used for traditional Tyrolean jackets.

In the first few years following the World War II, when large numbers of young people with limited financial resources were taking up skiing, the ski magazines were full of advice about acquiring equipment and clothing on the cheap. In 1951, pants cost between five and eight guineas and parkas, which had replaced the tightly-buttoned jackets of previous years, were around seven guineas. Falls Creek instructor Lorna Clarke, a frequent contributor to the Ski Club of Victoria’s monthly magazine, Schuss, suggested one rather alarming way of getting around this pecuniary obstacle:

Buy a pair of disposals jungle-green trousers, which will cost about 25/- and waterproof them in the following manner. Dissolve 4oz. of lead acetate in a half-bucket of warm water, and ditto with 4oz. of alum in another half-bucket of warm water. Add the contents of the two buckets and allow the white precipitate to settle for some hours. Decant the clear liquid into one of the buckets and soak the trousers in this for half an hour. Then hang up to dry. Since lead compounds are poisonous keep everything well away from the kitchen. When the trousers are dry they will, of course, be non-dangerous. They will also be waterproof, and practically wind-proof.

Throughout the Forties and Fifties and well into the 1960s, big woollen sweaters featuring Fair Isle snow crystal patterns were immensely popular with both men and women and there were brisk sales of matching socks, mittens and head-bands knitted with greasy wool. However, the advent of rope tows saw the one-time craze for long scarves, as well as trailing hair and excessively loose upper clothing, decline rapidly, since the ropes had a malevolent tendency to twist, entangling clothing and other dangling items with resultant injury to the wearer.

Good quality leather gloves or mittens which kept hands dry as well as warm eventually ousted woollen mittens from ski shop shelves.

A small but essential item in every regular skier’s wardrobe was at least one pair of overboots. Lacing up double boots consumed much time and energy and few skiers were inclined to take off their boots at lunch time or during any other brief periods off the slopes during the day. At the same time, since moisture-resistant carpets and scuff-proof vinyl flooring had not yet been invented, most lodges had strict rules prohibiting ski boots indoors. The answer was overboots. As a rule, these were little more than pieces of tough fabric or plastic cut into an oval shape with elastic drawn through the hem like a shower cap. Indeed, many a Woolworths shower cap served duty as an overboot. More elaborate overboots had felt soles but most were simple slip-ons that could be carried in a parka pocket. They became obsolete when the introduction of buckle boots made it a simple matter to slip in and out of them when necessary.

When the gracious era of dressing for dinner in snowfields accommodation houses such as the Hotel Kosciusko and the Mt Buffalo Chalet ended after World War 11, along with the provision of porters to carry suitcases, it would be a long time before haute couture appeared once more in Australia’s apres ski bars, let alone on the ski slopes. Until access to most resorts improved to the point where skiers could either drive to the door or at least seriously consider using a suitcase once more, dressing – especially for apres ski – was limited to what could be fitted into a rucksack. ‘Real’ skiers looked sensible, rather than smart. As a writer in The Age cautioned Melbourne readers: Avoid sitting round for hours drinking coffee and don’t look too fashionable.

Wendy Cross was an active skier, ski patroller and ski administrator for almost 25 years, and contributed numerous articles on skiing to newspapers and magazines in Australia and Canada. She edited the Australian Ski Year Book for 14 years and is the author of a book covering the first 100 years of Australian skiing, published by Walla Walla Press in 2012.